Twenty five participants attended the course for global resource development for peacebuilding and development commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan and held by the Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center at the Olympic Youth Memorial Center in Tokyo.

Professor Hasegawa made a presentation entitled “UN Peacebuilding: Challenges for UN Peace Missions” and explained first how UN peace operations transformed in its approach during the last 60 years from 1948 to 2018. He then explained the twin challenges faced by UN peace operations on how to achieve better integration and national ownership. The following are excerpts of discussions that took place in two sessions.

This year the course had 25 program associates: 15 Japanese associates and 10 international associates from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Egypt, Iraq, Mali, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia. The course provided 6-week trainings in Tokyo and Hiroshima, and then Japanese associates will be deployed as a United Nations Volunteer (UNV) for one year.

This lecture consisted of two main topics:

- UN Peace Missions 1990-2018: Norms and Implementation Mechanism, and

- Duality of Challenges for Success Criteria: Integration and National Ownership.

The first session focused on how UN peace missions have evolved since 1948. To begin with, Professor Hasegawa asked, “What are UN peace operations?” One Japanese associate raised his hand and answered that UN peace operation includes conflict prevention, peacemaking, peace execution, peacekeeping and peacebuilding. On a side note, Professor Hasegawa gave him a key ring as a reward for speaking out in the class first. The professor emphasized the importance of speaking up in a multinational environment, particularly referring to the UN.

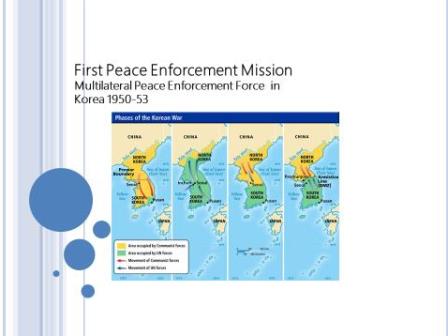

Professor Hasegawa then asked the second question, “What types of peace operations did the UN carry out during the period from 1948 to 2018?” We discussed three generations of peace operations. The first generation is inter-state peace operations, which focused its attention on separating two states in conflict. Peace was maintained through truce and ceasefire following an end to inter-states armed conflicts. The first generation’s peacekeeping has three traditional principles as its doctrine base: consent, neutrality or impartiality, and non-use of force except for self-defense. The professor referred to the multilateral peace enforcement in Korea between 1950 and 1953 as an example. In the Korean Peninsula, Kim Il-Sung, the founder of North Korea, officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), tried to unite the peninsula into one country with the support of communist powers. In March, 1951, the Security Council was convened, and the US and its allies passed the resolution against North Korea in the absence of Russia so as to establish a ceasefire in the peninsula. The Korean War has been ceased since then, but it has not been over yet with the demilitarized zone (DMZ) being kept between South Korea and North Korea.

In spite of multilateral efforts to maintain peace, the world witnessed disasters in the early 1990s including, for example, casualties of American soldiers in Somalia in 1993, the 1994 Rwanda genocide which killed 800,000 people and the 1995 Srebrenica massacre which resulted in death of 8,000 people. Professor Hasegawa was the director of the policy planning unit of UNOSOM II in Somalia in 1994. He told the participants that he went to Rwanda in 1995 and became the UN resident coordinator there because no one wanted to go to Rwanda when he went back to Geneva from Somalia. In 1995, the Kibeho massacre occurred in a camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) near Kibeho in Rwanda, and the professor talked about the story of the time when he had to walk on the field covered by bodies of its victims.

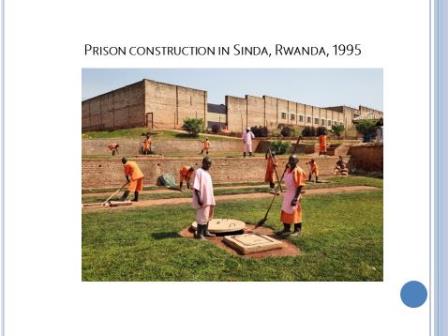

As a response to such intra-state conflicts, peace operations evolved into the second generation’s multi-dimensional peacekeeping efforts, the primary activities of which were civilian and humanitarian in nature. In the second generation, peace operations dealt with a whole state aiming at comprehensive peace agreements, which meant complex lines of operations and complex mandates (political, security, humanitarian and developmental) integrating civilian and security tasks under one political command. Professor Hasegawa mentioned some of his experiences in Rwanda as examples. For instance, as the resident coordinator, he was engaged in the establishment of Rwandan National Community Police composed of the Tutsi population. According to him, it was critical to change their mindset from that of an army to that of a community police. He also built a new prison in Rwanda because all the existing prisons were full and some prisoners had to stay outside which resulted in some of them losing their leg due to their rot in a tropical climate. Prisoners themselves were involved in building the new prison.

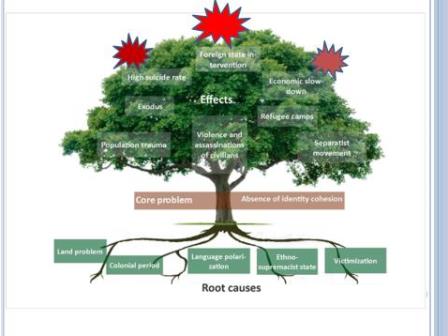

The third generation of peace operations was born as conflict and instability were increasingly seen as the result of weak or fragility of state. It focused its attention on peace and state building, reflecting new understandings of the requirements for peace building as identified in the Agenda for Peace promulgated by then Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali. They meant “comprehensive efforts to identify and support structures which will tend to consolidate peace and advance a sense of confidence and well-being among people.” The importance of addressing root causes of conflicts were emphasized and a belief in good institutions founded on the basis of democratic peace theory grew.

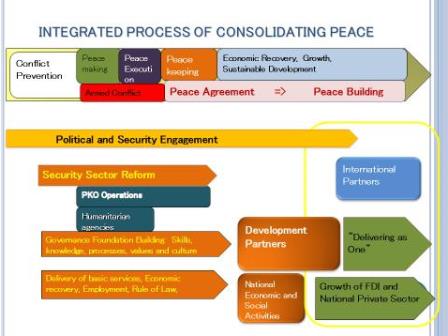

In the second session, Professor Hasegawa gave us the introductory lecture focused on twin components of the challenge that the UN has faced, which are integrated approach and national ownership. We then discussed what the UN has tackled on the ground in peacebuilding. Its answer was that the UN sends troops and civilians. Then, he identified two challenges and shortcomings of UN peacebuilding operations: one is lack of integrated approach in dealing with the demand for concerted efficient and effective operations. Another is lack of national ownership of the peacebuilding process as the international staff tend to do peacebuilding tasks themselves and national leaders and activities neglect their commitment to national interest. Professor Hasegawa concluded that sustainable peacebuilding requires the change of mind-sets of local leaders.

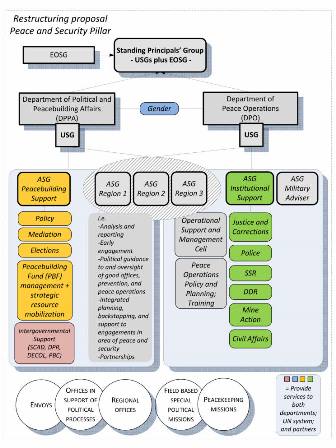

To begin with, Professor Hasegawa mentioned how four Secretary-Generals of the United Nations UNSG, namely Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Kofi Anna, Ban Ki-moon and António Guterres tried to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of UN peace operations, and then, opened with a question concerning various issues the UN has had to deal with. One of the latest approaches of the Secretary-General’s proposal is the need for more coordinated, coherent and integrated approach to post-conflict peacebuilding and reconciliation. Indeed, in 2017, the current UNSG Guterres embarked on UN reform which aimed at transforming the structure and working modalities of the UN system in order to overcome the shortcomings of the Organization. The reform focuses on a whole-of-pillar cooperation of all components, including politics, security, economy and justice. Specifically, his proposal emphasizes the restructuring the Department of Political Affairs, the Department of Peacekeeping Operations and the Peacebuilding Support Office, and related changes in the Organization’s working culture.

Here, Professor Hasegawa asked the participants from Africa how the local people had felt about the withdrawal of Japanese PKO contingent from South Sudan. One of them noted that the local people, who were benefiting from the Japanese infrastructural support, are sad about the withdrawal of its PKO engineering contingent. Japan had been contributing very much in the construction of roads and bridges. The Japanese withdrawal came after Kenya had withdrawn its troops from South Sudan. Hence, this might have impact on the overall operation of UNMISS, which is in need of more human personnel to boost its mandate for the protection of civilian and creating conducive environment for safe return of the IDPs.

Professor Hasegawa then asked the program associates about the relationship between ownership and accountability. Some associates responded, for example, be responsible to explain, pay for it, less corruption etc. Professor Hasegawa explained that the key to this question was whom you are responsible to. UN agencies and NGOs regard donors as providers of funds and tend to be attentive and responsible to the donor countries and agencies. Even the national leaders tend to be responsible and accountable to donors. However, the national leaders should be accountable to local people.

One of the associates asked a question whether democracy is the prerequisite for good governance. Professor Hasegawa responded that democratic principles and forms of governance are reasonable. The Greek philosopher, Plato, argued that democracy is inferior to monarchy, aristocracy and even oligarchy on the grounds that democracy lacks the expertise necessary to properly governed societies. Yet, democracy is the second best, following oligarchy, which is a government system ruled by enlightened monarchs or small groups of elites. For instance, Japan had around 260 years’ peaceful time in Tokugawa era from 1603 to 1867. Why was it peaceful for such a long period? This is because there were no external interventions against the regime. The society in the Tokugawa period was based on the strict class hierarchy: farmer 80% of the population, samurai (warrior) 3%, artisans 5%, merchants 5%. The acceptance of people as a whole to the hierarchical system of governance and lack of expectation among people about their social mobility. As people were not educated, they did not think have expectation to rise above their own status.

Today, not only in developed but developing countries, people world have access to the Internet and find out what is going on in the world. People cannot be kept ignorant about the current world.

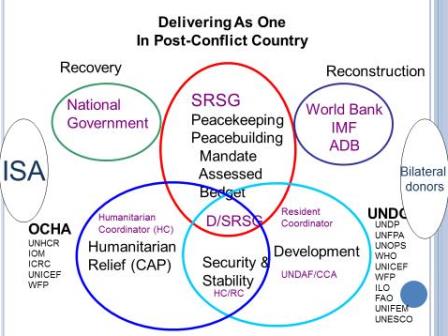

Concerning the pertinacious need for more coordination and integration of UN system-wide approaches and activities, Professor Hasegawa explained how the UN agencies have tried to “Delivering as One” as early as 1980`s when he was Deputy Resident Representative of UNDP in Nepal. Now, Secretary-General Guterres is calling for the integration of political, security, humanitarian and development activities. However, each organization tends to do what it wants to do for the benefit of the agency. We have to work and coordinate together, and share meetings even though the integration of inter-agency is very difficult because they would have different mandates, interests and goals (political, military, administration), different accountability to stakeholders and principles (humanitarian, human rights), or different command and control structure (security agencies). How would it be achievable? We should be credited with having a common interest. In effect, over the period of last ten to fifteen years, the UN reformed its mission structure and integrated RC (resident coordinator) with HC (humanitarian coordinator) into the UN peacekeeping and peacebuilding structure headed by the SRSG (special representative)

It is not easy to create and establish an effective integrated framework within the UN system. Personalities and institutional interests still overpower systematic approaches. Headquarters’ structures remain poorly aligned to support field integration. However, Professor Hasegawa pointed out that we have to seek to build capabilities, which are deployed to greatest effect, in support of an overarching peacebuilding strategy.

Professor Hasegawa then explained the philosophical idea of ethics, advocated by Immanuel Kant as “doing the morally right thing regardless of the outcome”. For example, a business firm make a financial donation of 100 thousand dollars in support of Rohingya refugees in order to increase its visibility and reputation as the company that does good things. Or the company donates funds to Kumamoto prefecture to reconstruct the Kumamoto castle, so that it would gain a good reputation while its hidden objective is to reduce profit and tax payment. These conducts are not right things to do in terms of Kant’s idea of what is a morally right thing to do.