Hasegawa considers the East Asian countries can learn from the successful reconciliation process carried out by the two countries which had fought for twenty-four years.

At the Club de Madrid round table conference held in Dili on July 30 and 31, 2017, Former President of Indonesia Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono explained how the truth and friendship process was successfully carried out by Indonesia and Timor-Leste.

As explained by Sukehiro Hasegawa in his book, Primordial Leadership: Peacebuilding and National Ownership, UNU Press, 2013, pp.162-94.

The UN and Timorese authorities established the following main institutions to address the issues of truth, justice and reconciliation:

- The Comissao de Acolhimento, Verdade e Reconciliacao (CAVR, Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation).

- The Serious Crimes Process (SCP).

- The Commission of Experts (COE).

- The Commission of Truth and Friendship (CTF).

The Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (more commonly known by its Portuguese acronym CAVR: Comissão de Acolhimento, Verdade e Reconciliação de Timor Leste) was established on 13 July 2001. This was an independent entity with the objective of investigating human rights violations committed by both sides, i.e. both Indonesian and Timorese entities. The period of investigation was a total of 25 years from April 1974 to October 1999. CAVR was also tasked with facilitating community reconciliation for those who had committed less serious offences.4. In doing so, it was to help establish the truth about these violations, and carry out the process of reconciliation aimed at restoring the human dignity of victims. It was not a prosecutorial mechanism. CAVR was, however, empowered to refer serious crimes of human rights violations for prosecution.

The CAVR was an independent truth commission established in East Timor in 2001 under the authority of UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET). Japan provided financial assistance for physical establishment of its secretariat office in the Comarca, a former Portuguese and Indonesian prison.

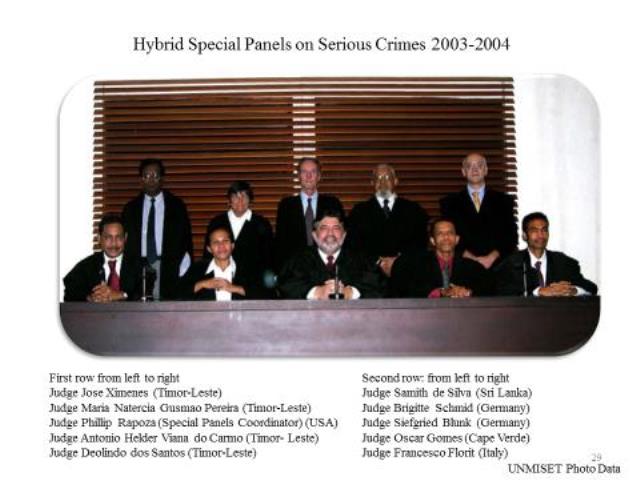

The Serious Crime Process consisted of judicial activities undertaken by three units: the Special Panels for Serious Crimes (Court), the SCU (Prosecution) and the Defence Lawyers Unit. The Court was headed by Judge Phillip Rapoza of the United States.

The Commission of Experts were appointed in order to identify the obstacles and difficulties encountered by the two entities and to evaluate the extent to which the two institutions had been able to achieve justice and accountability for the crimes committed in Timor-Leste.

Indonesia and Timor-Leste created the Commission of Truth and Friendship (CTF) in August 2005, in order to establish conclusive truth, with a view to promoting reconciliation and friendship between the two countries. The United Nations rebuffs the Commission of Truth and Friendship (CTF) Both the Governments of Indonesia and Timor-Leste wanted to set aside the past and move on to the future. For this purpose, they agreed to create a unique body, the Commission of Truth and Friendship (CTF) in August 2005, in order to establish conclusive truth, with a view to promoting reconciliation and friendship between the two countries. This also signified that, for the first time, the two countries had decided to create and own a truth-seeking mechanism instead of following the advice of the United Nations and the international community. The emphasis was on reconciliation. Truth was to be established so that it could be a foundation for building a friendly relationship between the two countries.

The bilateral Commission commenced its work almost immediately, embarking upon the analysis of documents provided by the Ad Hoc Human Rights Tribunal in Jakarta and the records compiled by the SCU in Dili. The mandate of the CTF, initially extending over a period of one year, reflected the forward-looking and reconciliatory approach taken by Timor-Leste and Indonesia.

Ten Commissioners – five Indonesians and five Timorese – were appointed to: reveal the factual truth of the nature, causes and extent of reported violations of human rights that occurred in 1999; issue a report establishing the shared historical record of the reported human rights violations; and devise ways and means as well as recommend appropriate measures to heal the wounds of the past, and to restore human dignity, by recommending inter alia amnesty, rehabilitation measures, means to promote reconciliation and innovative approaches to enhance intra- and intercommunal cooperation.

The controversial provision contained in the CTF’s charter was a clause granting immunity from prosecution based on the testimony to any person testifying before the Commission. This was in line with the approach taken in South Africa. The UN Legal Office maintained that it would not approve the CTF or provide it with support as long as the immunity clause remained in its charter. The leaders of Indonesia and Timor-Leste eventually decided to launch the Commission without the support of the United Nations.

On 31 May 2005 I met with President Gusmão, who was confident that the CTF would establish the truth, and that it could complement the work of the SCP. He clarified that it would not be holding trials. He then emphatically stated that the revelation of truth was, under the prevailing circumstances, the best approach towards the development of the country, given that the State of Timor-Leste assumed the principle that this was a way of achieving justice. Gusmão insisted that the key lesson learned was not to allow the recurrence of political violence in the country under any circumstances. He added that, if the SCP were to continue in Timor-Leste, it would complicate matters. Therefore, he suggested that, if the international community wished to continue the process, it should be held outside of Timor-Leste. President Gusmão was also of the view that it was futile to prosecute and indict individuals. He then informed me that the Timorese Commissioners of the CTF had been identified and would include Aniceto Guterres, Head of CAVR, and Jacinto Alves, a CAVR Commissioner. The President hoped to have the CTF functioning no later than August 2005. He then said that he would welcome international legal and human rights advisers attached to the CTF, and expressed the hope that the United Nations and the international community could provide advisers to support its work.

During the subsequent weeks, further consultations took place concerning the membership of the CTF. On 1 August 2005, Foreign Minister Ramos-Horta convened a meeting with the diplomatic corps and announced the final list of five Timorese members of the CTF. Ramos-Horta emphasized that in accordance with paragraph 16 of the TOR, Timor-Leste selected personalities of “high standing and competence”. They were:

- Mr Aniceto Lopez Gutierrez, a lawyer, former Head of CAVR, and an outspoken human rights advocate;

- Mr Deonisio Babo Soares, lawyer and anthropologist, and former Programme Director of the Asia Foundation;

- Mr Jacinto Alves, CAVR staff member and human rights activist;

- Ms Felicidade Guterres, resistance activist, former member of the ConselhoNacional de Reconstrução de Timor (CNRT, National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction) and World Bank staff member; and

- Mr Cerilio Christopho Varadales, lawyer, and one of the country’s leading judges.

The Minister also announced the names of three alternative Commissioners. Although the TOR for the CTF did not provide for alternative members, both countries had agreed on their appointment in case of illness or absence of the original five Commissioners. The Foreign Minister insisted that the selected members reflected integrity and full independence from both governments. They would exercise the greatest efforts to get to “the bottom of the truth” in fulfilment of their mandate, while staying within the respective constitutional contexts.

Referring to the need for technical assistance and research support, Ramos-Horta stated his intention to recruit two international advisers, and sought support from the international community. I proposed that the Minister send an official letter for my attention so that I could officially follow up on the request. The diplomatic corps was then given an opportunity to pose questions in order to clarify a number of issues, including the physical location of the joint Secretariat; this was to be established in Bali. We also discussed the submission of a progress report to the governments and heads of state every three months. Ramos-Horta explained that with the official announcement of the members of the Commission, the CTF was to begin by establishing its organizational structures, including staffing, office allocation and administrative procedures; a detailed work programme for the duration of its mandate was also to be established. He further emphasized that while the Commission operated independently, the two Foreign Ministers would observe the work of the Commission closely in order to provide advisory or other assistance as required. The Governments of Timor-Leste and Indonesia were contributing $500,000 and $1 million, respectively, to the CTF budget.

The CTF would conduct its work using the material gathered by CAVR, the SCU and the Ad Hoc Human Rights Court in Jakarta. The American Ambassador, Grover Joseph Rees, congratulated the Foreign Minister on his choice of Commissioners, as they were people of great integrity and intelligence. In order to facilitate contact, I asked the five Commissioners to identify a focal point for interacting with the United Nations and diplomatic corps. I felt reassured by the Foreign Minister’s emphasis on the importance of upholding transparency throughout implementation of the entire mandate, and by his confirmation that the Commissioners would remain at the disposal of the international community for any future queries pertaining to the work of the CTF. On 2 August 2005, Ramos-Horta came to visit me. As usual we began by talking about a variety of issues of mutual interest, and then discussed in depth the need for international assistance to implement the mandate of the CTF. He handed me a letter inquiring about potential UN support, and pointed out the need for recruiting two international advisers to assist the CTF. He stressed that the “institutional memory” of the two advisers, and their experience in the field of human rights and justice in the country, would be indispensable for effective and successful implementation of the CTF mandate. I agreed, and told him that I recognized the need for international advisers to maintain the professionalism of CTF’s work, assuring him that I would forward the request to UN Headquarters. I then mentioned to Ramos-Horta the need to complement the Commission’s mandate with an effort to deal with the return of former militia members who had been indicted under the SCP. I explained that in my opinion this would greatly contribute to greater national ownership of the process. Ramos-Horta understood my reasoning and told me that he would discuss this possibility with the Prime Minister and the President. He also noted that follow-up decisions, taking into account the constitutional provisions of both countries, had to be made by the National Parliaments of both Timor-Leste and Indonesia. Referring to concerns raised about the provision of amnesty to ex-militia, he was cautious that amnesty would only be recommended in case of collaboration with the truth-seeking process. The actual amnesty would be granted only with Parliament’s approval. On my part, I emphasized the importance of conducting a credible process. The CTF had to prove that it was not meant to gloss over the past, but to prepare the two countries for an amicable relationship. I told him that some sources in the international community were indeed concerned that the CTF process would avoid naming names in favour of ascertaining “institutional accountability”. Taking note of this concern, Ramos-Horta spent much time elaborating on how he had impressed upon Indonesian Foreign Minister Wirajuda and other Indonesian authorities the importance of carrying out a credible process. He referred to the appointment of the Indonesian Commissioners as reflecting the good intention of the Indonesian state. Furthermore, he stated that as the reputation of Heads of State was at stake, both sides would make every effort to bring the CTF’s mandate to a successful completion. As we were finishing the meeting, I commended Ramos- Horta for his relentless efforts in building the cordial relationship between the two countries. I urged him to ensure that Timor-Leste and Indonesia serve as a leading example for achieving reconciliation between two formerly hostile states, based on truth and justice.