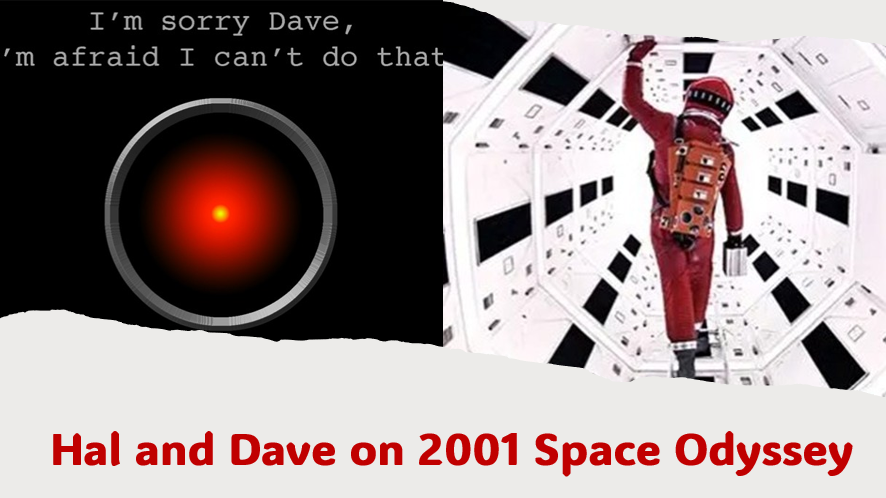

At the end of 2025, on SWISS flight LX161 from Narita to Zurich, I had the chance to watch the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Made more than half a century ago, the work still poses powerful questions today about the relationship between artificial intelligence and human beings.

What stayed with me most vividly was the scene in which HAL, the computer responsible for controlling the spacecraft, refuses astronaut Dave’s request—an entirely natural human act: rescuing a crewmate. HAL is calm, logical, and perfectly consistent. Yet its decision discards human life as an “obstacle to mission success.” The scene symbolically illustrates how an artificial intelligence may possess highly advanced, consciousness-like information processing while still lacking conscientious judgment.

What is being tested here is the difference between “consciousness” and “conscientiousness”—conscience and responsibility.

Consciousness, in this context, is the capacity to perceive a situation, process information, and reach rational decisions. Today’s AI is steadily acquiring abilities that, in this sense, approach—or even surpass—those of humans. But this is not the same as conscience. Conscience is an ethical capacity: to assume responsibility for what one’s actions mean for others, and to restrain oneself from crossing a line that must not be crossed as a human being—even when doing so runs against efficiency or rational calculation.

For this reason, I strongly feel that the foundational principle articulated by Immanuel Kant—“human beings must never be treated merely as means, but always as ends in themselves”—must be reaffirmed precisely in the age of AI. Technological progress does not replace human judgment and responsibility. It must, by its very nature, support and complement human dignity.

And yet in recent years, the civilizational consensus surrounding “human dignity” has begun to waver. Norms such as international human rights, democracy, and the rule of law are increasingly relativized—or even rejected—as a “Western construct.” It is true that liberal democracy as an institutional form emerged within particular historical contexts. But to leap from that fact to relativizing the ethical principle that “human beings must not be treated as tools” is a grave error.

This is because the principle is not a uniquely Western invention. It is one of humanity’s oldest moral insights, shared across civilizations. Kant expressed it in the language of reason and autonomy; Confucius located it in human relationships through the concept of ren (humaneness). Buddhism has offered compassion for human beings as fellow sufferers as a guiding constraint on action. Their expressions differ, but they converge profoundly on one point: we must not sacrifice human dignity for the sake of efficiency or power.

Today, the reality in which lives are treated as variables in strategic calculations in war, labor is handled like a disposable commodity in the economy, and human judgment and agency are being pushed to the margins in the name of “efficiency” in AI—this is the same ethical mistake repeating itself in new forms. HAL’s error does not remain confined to fiction.

Global governance in the twenty-first century cannot be sustained by legal frameworks and technical management alone. It must be grounded in an “ethics of restraint”—a civilizational understanding that progress and rationality are justified only insofar as they serve human dignity. I feel a deep sense of alarm at the growing tendency among leaders of powerful states today to act as if they were proxies for AI: proceeding without moral judgment, following data and immediate interests.

The United Nations was, in essence, an attempt to embody this shared ethical wisdom of humankind in institutional form. Its future significance does not lie merely in organizational reform. It depends on whether the UN can once again raise human dignity as the non-negotiable core of the world order.

In the age of artificial intelligence, what we truly need is not smarter machines.

What is demanded is the responsibility of human beings themselves—to act not only with consciousness, but with conscience.