PM Shinzo Abe takes Paul Krugman’s suggestion and is proposing fiscal demand stimulus at Ise-Shima G7 Summit.

Now we would like to start the third analysis meeting on international finance and economy, inviting Professor Paul Krugman of the City University of New York. Prime

Minister, please the floor is yours.

This is the third meeting of the analysis meeting on international finance and economy. Allow me to provide my greeting. Now, a Nobel Laureate and the former member of the Presidential Council on economic advisers, we have invited Professor Paul Krugman of the City University of New York.

Thank you very much for coming to this meeting.

Professor Krugman hitherto on the subject of the economics, you have provided various suggestions and proposals. In this meeting, we would like to hear your view on the analysis of the world’s economy, at the same time, since the start of the administration we have introduced the policy on three arrows. And also, we have come up with new three arrows in the face of the aging society with low fertility.

In May of this year, we are going to be the host of the G7 Summit at Ise-Shima looking toward the forceful growth of the world economy. We would like to transmit and communicate a strong message. This meeting would be a forum which will prepare grounds for the Ise-Shima summit in May of this year. Thank you very much.

Thank you very much, Prime Minister.

Professor Krugman, the floor is yours. Your initial remarks, please.

I believe I should just say a few words before we close the meeting, just to basically be thankful of the honor of being asked to address this group and to speak about these issues. It is a difficult world economy, unfortunately for now almost 8 years there have been no easy times for any of us. We are all very much wishing, I am a great admirer of the policy moves that have been made by Japan, but they are not good enough, partly because all of the rest of us are in trouble as well. So, again I am very honored and pleased to be asked to speak about the things that could be done looking forward.

Thank you very much, Professor Krugman. I would like to ask the members of the press to leave the room.

So, without further due, Professor Krugman, can you make a presentation?

I really want to make four points. The first is that we are now in the world of pervasive economic weakness. In many ways, we are all Japan now. This complicates policy for everyone including Japan. The second is that the linkages among major economies are strong. They are stronger than much conventional economic discussion suggests, largely I would argue because of capital flows. This is very important to speak about. The third, which may be of particular concern here is, we are seeing the difficulty in achieving goals through even very bold and unconventional monetary policy. Kuroda-san here, we will clearly need to speak about that. The fourth then is that monetary policy needs help from fiscal and possibly other policies but certainly on the fiscal side, and certainly does not need to be struggling against fiscal policy moving in the opposite direction. That is not just a Japanese issue but very much a global issue at this point.

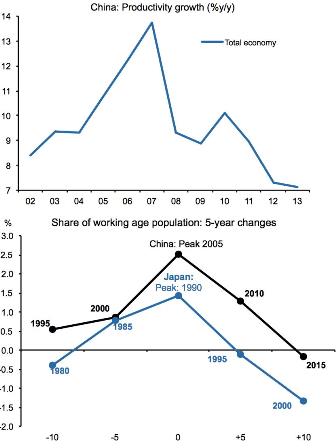

So, let me enlarge on those points and say a few things about what follows from them. The weakness, if you like the Japanification of other major economies, is…that is unfortunate we are using that phrase but I think it is useful here…is, quite significant. The Euro area looks a great deal now like Japan circa 1998, 1999. The fundamentals are similar. Working age population is shrinking. Technological drivers of investment do not seem strong, there appears to be just persistent weakness. Although the European Central Bank is run by a very smart person and very effective one, they have been unable to achieve their inflation targets. Despite the occasional periods when the European economy looks better, it does appear to be a situation of…that growth, to an increasing extent, looks like the notion of the secular stagnation, persistent weakness despite very easy money. The US looks better, has done much better, but we need to put that into perspective. Employment growth has been good but output growth not so much and there are signs that we are importing the weakness. Inflation is still below target and wages are not going much of anywhere, which suggest that we are not doing too well and for reasons I will explain in a moment. There is a reason to think that we will be dragged back by the problems elsewhere. And emerging markets are in big trouble, most particularly, the biggest emerging market which is right next door to you.

China has been simmering with known for several years that there was going to be a big problem of adjustment, as it was no longer able to sustain that very high investment economy. They have not yet found a way to deal with it. The policy in China seems quite erratic, which is not a good sign, given what is happening. The interdependence of the major economies is, I will argue, very large. Ordinarily, the view that I and others have is that the interdependency is limited because even now international trade flows are not that big. Even now, each of the major economies exports only a few percent of its GDP to the others, but the effects are much larger if the perception of investors is that weakness is sustained. If the Euro area’s problems are seen not as a problem just for now but as a problem for a very long period of time, then Euro area interest rates become very low even for long maturities. Right now, the 10 year German bond is about two tenths of a percent. That means that any economy that appears stronger is a likely recipient of large inflows of capital which drive up its currency, make it uncompetitive and cause them to share in the problem. You can see that the dollar has risen drastically. Even economies that are not too happy with their position, may find themselves recipients of capital inflows from other countries, or find that their own efforts to expand or somewhat undermined. So, we see, despite everything, despite everything that Mr. Kuroda is doing, the rise in the yen, which is a very unfortunate development from Japan’s point of view, is driven by the weakness of other major economies.

There is a special issue involving China. China is in big trouble. China which seemed to be a source of strength but also not very long ago we were accusing China I think correctly of manipulating its currency to keep it down. China is now in fact intervening to support its currency in the face of huge capital outflows. We believe that the capital flight in 2015 was about one trillion dollars. China has immense reserves but not infinite reserves, which mean that depreciation of the renminbi becomes a real prospect and that will make life very difficult for the rest of us. So, all of this interdependence is there.

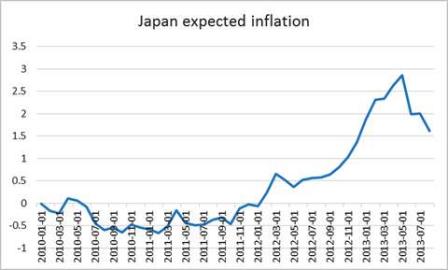

Monetary policy has been, in most places, the only game in town. It’s their line because fiscal policy has been politically paralyzed. Here, less so, but still in fact, of the three arrows by far the largest, so far has been monetary. Mr. Kuroda has done most of the lifting here. We are seeing the limits of monetary policy. We are seeing that it becomes difficult when you try the unconventional methods, we can argue this but it seems to be having diminishing effect. Negative interest rates, it is remarkable that that turns out to be possible. I do think it was the right move to make but it is very hard to push it further. The effects are proving to be limited. If we look elsewhere, if we look in Europe, despite another very able essential banker, the ECB seems to be losing traction. Here, as you know better than I, inflation expectation seems to be fading. Wage growth is not what it should be. We are seeing that the policy that has been the principle lever for trying to deal with this global weakness is not as effective as we had hoped and not as effective perhaps as it seems to be recently.

Fiscal policy. Everything we have seen for the past seven years suggests that fiscal policy remains effective, especially effective in these circumstances. It has been very difficult to apply it, a few years of bad debt, political conflict, the Europe is divided among counties, the United States is divided between parties, but fiscal policy is effective and the global environment right now is one where economies really, really need fiscal support. The idea that one should be prioritizing long-run budget issue over fiscal support now seems to me to be extremely misguided. Obviously I am talking about the consumption tax here.

Two points are following on all of that. You notice that I did not say anything about structural reform. That is not because I am against it but because structural reform seems largely beside the point on this crucial issue of boosting demand. Some kind of structural reform might spur private investment, which is good but that is rarely what is emphasized. Some other kinds of reform, the Abenomics, by expanding the future labor force helps to offset the demographic headwinds that the economies face. So all of that is good but I do worry that sometimes the talk of structural reform becomes an excuse not to deal with the primary immediate issue of sufficient demand, of fighting deflation or low-flation, inadequate inflation, which has got to rely on monetary policy.

But as I said, that has limits and on fiscal policy which needs to be more focused on that immediate need than it has been.

A last point, it is very important, I would argue, in this circumstance to understand that the risks are asymmetric. It could be that I am being too pessimistic and that things are going to be all right and demand would be stronger and there would be spontaneous recovery. It could be that things are even worse than I am portraying, that China is going to experience an explosive collapse, or simply that demand is going to be weaker than even my rather downbeat projections.

The consequences in those two circumstances are very different. If the world economy starts growing and inflation picks up, we know what to do. Mr. Kuroda, Mrs. Yellen, Mr. Draghi have had the tools to deal with that, no problem. If the world turns out to be weaker, then we are in deep trouble because we do not have effective tools, which mean that it is very important to err on the side of being more expansionary. This is an argument that my old colleague Larry Summers has made many times and I make it also. It is not simply what you expect to happen but what happens if you are wrong in either direction. It is very, very important to leave room in case you should be wrong on the downside.

So, this is the time for expansion. It should be coordinated as much as possible. I know the G7 Summit is coming up. Ideally we would have everyone agreeing on a coordinated fiscal expansion, in practice, that might mean Japan and Canada. I am not sure anyone else is prepared to deliver at this point but we can certainly try to have the language push in that direction. Japan itself needs to remain focused. The original goals of Abenomics are still the primal. Breaking out of that deflationary cycle is “Goal Number 1”. Everything else should wait upon that. Now I will throw it open.

Thank you.

Thank you very much, Professor Krugman. So you saved a lot of time for us so let’s have a good discussion from now on.

About two years ago, I had a pleasure meeting with you, Professor Krugman. At that time, Japan was able to be going out of the deflation then we have set for ourselves the 2% inflation goal. We were talking during that time that a rocket has to go out of the atmospheric region, which means that an escape velocity has to be earned in order to lift the Japanese economy out of deflation and we were looking for a good speed to do that.

That was a priority that we have been talking about. Hence, the rest of the world has been thinking about the fiscal spending and Japan should also come up with the fiscal spending in a coordinated fashion. We have been talking about that. But we worry about the accumulated debt.

That is a source of another concern. What to do about it?

But Governor Kuroda took a policy to introduce negative interest rates so that the 10 year JGBs yield turns negative at the moment.

So, we would like to take advantage of this situation and Japan should come up with a fiscal spending. That is what some of the people are saying right now within Japan. Do you have any view on this? Any observation on this point?

Very much so. The case for spending now is quite strong despite the debt. It is true for multiple reasons. First, fiscal stimulus is very important as an aid to monetary policy in breaking out of deflation. We have seen that it is difficult to do it with money alone.

Second, interest rates are very low. In fact, real interest rates in Japan are negative out

to very long maturities. There are needs, there are spending that needs to be undertaken. A business faced with very low borrowing cost and with real investment opportunities would find this a good time to spend. That is true even for Japan. Third point I would make is that the concerns about the debt, I don’t want to wave away entirely but one thing we have learned from Japan but also from other advanced countries is that stable advanced nations that borrow in their own currencies have a very long road for them to have a fiscal crisis. People have been betting against JGBs since about 2000. All of them have suffered financial disaster. The robustness of the market is very strong. It is even hard to tell a story. If someone says Japan would be like Greece, tell me how that happens. You have your own currency. The worst that could happen would be that the yen would depreciate which would be a good thing from your point of view. I do not think that is a thing to be worried about. Finally, to the extent we are concerned about the long-run fiscal position. One of the problems of deflation or inadequate inflation is that at least Japanese real interest rates being too high. And the way to break out of that is to get a sustained positive inflation rate. As all of you know, I would like it to be above 2. But whatever the number is, you need to achieve that. Compare with that goal what the budget balance is over the next two or three years is of much less importance. In fact, the low interest rates right now mean that the weight of the future position which depends upon breaking out of deflation is much higher compared to the current budget. I would say, this is not a time to be worried about the fiscal balance.

Thank you very much. Minister of Finance, please?

During the 1930’s, I remember that in the United States likewise there was a situation of deflation. And the New Deal policies have been introduced by then President Roosevelt. As a result, it worked out very nicely, but the largest issue associated with it is that for a long period of time entrepreneurs and managers of companies did not go to make a capital investment by receiving the loan. It had continued up until the late 1930’s and that is the situation occurring in Japan too. The record high earnings have been generated by the Japanese companies but they would not spend in the capital investment. There are lots of earnings at hand on the part of the corporate in Japan. It should be used for wage hike or dividend payment or the capital investment, but they are not doing that. They are just holding onto their cash and deposits. Reserved earnings have kept going up. A similar situation had occurred in the US in the 1930’s. What solved the question? War! Because World War II had occurred during the 1940’s and that became the solution for the United States. So, let’s look at the entrepreneurs in Japan. They are stuck with the deflationary mindset. They have to switch their mindset and should start making capital investments. We are looking for the trigger. That is the utmost concern.

The important point about the war from the macroeconomic point of view is that it was a very large fiscal stimulus. That fact that it was a war is very unfortunate. It was simply something that led to a fiscal stimulus that would not otherwise have happened. In fact, the story in the 1930’s was that the New Deal, Roosevelt backed off the fiscal stimulus in 1937, because then, as now, there were many calls for balancing the budget. That was a terrible mistake. It caused the major second recession. Yes, obviously we are looking for ways to achieve something like that without war. There has been a good deal of talk about using not just moral suasion which has already been done perhaps as an incentive to induce the private sector in Japan to raise wages. I have no knowledge of the institutional details about what might work but I am certainly in favor of trying such measures. That is one thing that can happen. Other than that, the linkage between corporate earnings and corporate investment has always been weak. There has never been much reason to expect companies that have high profits to also invest, unless they see reason to expand capacity. And what is happening is that they have the deflationary mindset. They believe that Japanese growth will be weak. Clearly if we look at the behavior of wages, they expect, or at least fear, that Japan will slide back down towards very lower negative inflation. What is still needed is a shock to break that. That is escape velocity. This is part of what I mean by escape velocity by achieving enough. Escape velocity: the rocket that goes fast enough to not come down again.

Well, talking about Japan, in 2014, the consumption tax rate was raised from 5% to 8%. There was a last minute demand which came in. So right after that, we had seen a dampening effect on consumptions. We are still having a lingering effect. We are thinking about the further rise in the consumption tax rate which was deferred by one year and a half but in case of Europe, as for the VAT raise, maybe in the European situation, the impact was not as large as that in Japan. Why such a big impact in Japan? Because deflation continued for a 20 year period. Moreover, it is not a deflation situation anymore but we have not completely gotten out of the deflation. Do you think that is the reason that we are stuck with this kind of situation?

I am not certain why the VAT hike did so much to arrest recovery in Japan. It may be that it was the public viewed it as a signal that the policy would not be expansionary, that it was a break in what had seemed to be a run of all expansionary measures, but I do not know that. I would say that Japan does have some fundamental reasons for why it is hard to raise demand. The demography in Japan is uniquely unfavorable and the working age population is now shrinking at more than 1% a year. Now, Europe has moved in the same direction and even in the United States we have seen a sharp deterioration of working age population growth. But there are reasons why Japan has special difficulties. Essentially, there is a reason why Japan entered this situation in the 1990’s when the rest of us did not enter it until 2008. But that does not mean that it cannot be dealt with. It just means that there are needs of extremely vigorous sustained aggressive policies to break out.

Regarding fiscal stimulus measures, I think there are some G7 countries which have enough policy space for fiscal stimulus, like Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom. But as you alluded, none of them are likely to implement significant stimulus measures in coming months. How do you think we should argue for further stimulus measures in those countries with enough fiscal space?

It is very difficult to make the argument. In the case of Germany, they simply live in a different intellectual universe, very difficult to talk about this. In the case of the United States, I assure you that President Obama favors increased infrastructure spending. In fact I can actually say that there was one meeting of economists which he opened by saying, “I want to hear your ideas. Don’t tell me we should spend a trillion dollars on infrastructure. I know that, I can’t get it through congress”. So, the US has that problem. Still, believe that it is the case that at the very least, we can blunt the push for fiscal consolidation. There is some role of persuasion between the countries. My sense is that conventional wisdom, sentiment among, if you like, the policy community, has been shifting in the direction of seeing again the case for stimulus and it might be possible to move that along. About my own country, we have an election coming and something really terrible could happen in the election. But it is also significantly possible that we will, at the end of this year, have a legislature that is significantly less obstructionist than the legislature that we now have. So, the United States may be a more helpful partner on macroeconomic policy. I certainly hope so.

There has been the declining of the commodity prices which had hit big blow on the developing countries in particular. Do you have any outlook on the impact coming from the declining commodity prices? What would be the impact expected upon the economy? Can I ask you?

The impact is very severe on some emerging markets. It is interesting to know that the most important, biggest emerging market, which is China, is a commodity importer. So, on the whole, it is actually favorable for them but very severe consequences for Brazil and for Africa. Those are important stories because there are a lot of people involved, not clear how much the backwash to advanced countries is from that economically. We would think we can worry about geopolitics. One unfavorable surprise has been that the fall in oil prices are not the positive thing that we had once thought, at least not as positive. The reason has a lot to do with the fact that, the very thing that has brought oil prices so low, which is the rise of “fracking”, means that the energy is an important investment sector in the United States especially, and the drop in oil prices, although it encourages consumption hits investment and so it is much less of a positive than it once was. My story, however, would be that the commodity price decline, although a huge thing from the point of view of understanding geopolitical developments, very important for a large number of people in the world, is not that big a part of the problem that we are facing in the advanced world, that the problem is instead these demand issues. I mean, it is shocking what has happened to commodity prices but that is not where the downdraft on our economies is coming from.

Now, on the subject of EU, European community, there are people with the pessimistic views. Within the European Union, they have the single currency and because of that there was the Greek problem. Other countries had the only limited options in terms of policy in those countries. Fundamentally, the Greek problem will persist within the European community according to some people. How do you see the situation?

This is a very severe problem and not being resolved. The Euro is a major constraint, not just on Greece but on much larger economies as well. France would have fiscal space for expansion. It really is not a serious trouble at all except that because of the Euro, it feels that it does not have that strength, that ability to move. I would argue actually that it could but it is certainly much more difficult. If France had its own currency, there would be no question. France is able to borrow at interest rates only 30 or so basis points above Germany. They are not a country which has difficulty raising funds but because of the constraint of the Euro, they are not able to move. That, just right there, you would have a much stronger position. The trouble, I think, with Europe reaches beyond the Euro. In fact in Europe right now, the economic issues have almost been pushed into the background by the refugee crisis, which is bringing about a crisis also in Schengen, in the open borders. This is in a way similar to the Euro. It is the incompleteness of the European project. They created a very open integrated system without the institutions necessary to make it work, which leaves Europe rather paralyzed and contributes to the problems we all have. In effect, the only effective player on European policy is Mario Draghi at the European Central Bank who was a very good player but has limited reach without any government really behind him. I should mention, just as one more thing to worry about, there is a quite significant possibility that Britain will vote to leave the European Union in a couple of months. This will add to uncertainty and is a further drag on the world economy. If we are going to say which members of the G7 are really able to move effectively and seem to be clear-headed, at the moment it would be basically, I think, Japan and Canada. We have excellent leadership at the top of the United States but then we have a crazy congress, so it makes life difficult.

Other questions from other members of the meeting? Prime Minister? Would that be alright?

Well, this time around, at the G7, how we analyze this situation, of course, we have to have a thorough discussion going forward. Professor Krugman, international community must coordinate in the fiscal space and the countries which are able would spend fiscally. This message is very important. I presume that this is going to be essentially your message and I agree with your message. So, we will coordinate and collaborate with other countries. Of course, countries have variety of their issues and their situations. After all, this is off the record, Germany has the greatest space for a fiscal mobility. Going forward, I plan to visit Germany. So, I will have to talk to them and I will have to persuade them how they will come along with the policy for further fiscal mobilization. Is there any idea from you?

It is difficult and let me say also that Chancellor Merkel is preoccupied with other matters as well, which she has been very good but it is an impossible situation. There is one thing that I think I should have raised, one area where there might be a possibility of getting, at least raising something that might be an accessible form of stimulus, which is that in fact climate policy, in addition to being, of course, crucial, in some ways nothing else matters compared with that, is also a possible incentive for private investment as a shift to green technology across the advanced world. Perhaps at least some statement about the desirability of moving forward, we have the Paris ACCORD that may be one route on which things can happen. I wish I had better suggestions. A brilliant diplomacy is not something I am an expert in.

Certainly, climate policy would be one area, which will stimulate further private investment. So, we would like to discuss along those lines as well. For example, Germany, because of the refugee question, investment, for example, housing investment for refugees or educational investment for refugees, do you think that would be effective in terms of fiscal policy?

Yes, it is a stimulus. I think if you actually cost it out, it is not very large. The refugee issue creates enormous tension because of social fears but if we can say, though strange way to put it, taking care of the refugees does not actually cost enough to be a major fiscal stimulus. It is not trivial but it is not that big. When we were looking at it, I know that President Hollande was speaking about we should lift the fiscal restraints in order to deal with this crisis. For a moment we are all kind of excited saying this is the end of austerity but the numbers just did not seem to be big enough to actually be a really major departure. If you are looking for the fiscal equivalent of war, it is not that. It is tremendous social political strain but not in fact that much money.

Professor Krugman, thank you very much. Thank you very much for the valuable advices today. Secretariat, we are holding a press briefing right after this. I hope you agree with us. Of course, what was mentioned by Prime Minister will remain confidential. Thank you. I thank everyone for coming.