According to a report filed by Susan Manuel of PASSBLUE, China`s influence on the process of constructing the new structure of UN peace and security architecture in growing. Please see below her report.

UN Budget Committee O.K.’s Major Reform of the UN, as Peacekeeping Is Squeezed

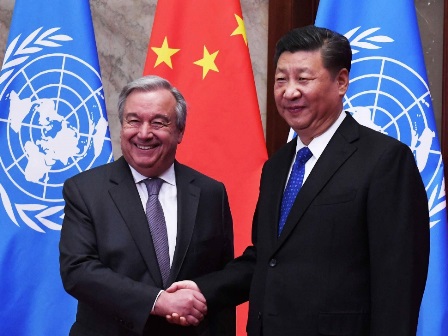

Secretary-General António Guterres visiting a training center for UN peacekeeping police, located in Hebei Province, near Beijing, April 9, 2018. Through major reforms, he is striving to remake the UN to save it. YUN ZHAO/UN PHOTO

The United Nations has been given the green light from its 193 member nations to embark on a major overhaul of its operations, based on a trio of reform proposals put forth by Secretary-General António Guterres in the last year and recently agreed on by delegates. The changes — primarily affecting the world body’s peace and security work globally and revamping the management of the UN — represent the most significant shift for the system in decades.

The main budget arm of the General Assembly, called the Fifth Committee, informally approved on June 30 a large part of the spending requests for two elements of Guterres’s reform agenda after national delegates lobbied in a series of closed sessions since early May. The changes to the UN boil down to the reorganization of its peacekeeping and political affairs departments as well as streamlining the UN management structure, affecting the 38,000-staff organization in New York and around the world.

The third element of Guterres’s reform agenda, restructuring the UN’s vast development network, did not fall under the purview of the Fifth Committee because it will rely on a voluntary fund.

As part of the reform package, the Fifth Committee — one of the most powerful entities in the UN but one of the least understood — agreed on an overall spending level of $6.7 billion for peacekeeping operations for 2018-2019, after negotiating proposed costs for most of the UN’s peace missions. (The $6.7 billion includes maintaining the UN mission in Darfur, Sudan, for six months, until a yearlong budget for it is approved in December, as the mission winds down. That could kick the overall level to about $7.1 billion.)

Guterres had asked for $7.3 billion for peacekeeping (including Darfur); that is about $47 million less than last year’s budget, as three operations closed in the past term. A big reduction for peacekeeping also occurred in the budget for 2017-2018, when American-led cost-cutting efforts resulted in a decrease of some $600 million from the previous year.

The 2018-2019 proposed budget must be adopted by the General Assembly, which could happen this week. The proposed cuts will hurt the missions in Africa the most, with those in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, Mali and Central African Republic taking the biggest hits, in that order. Allocations of budgets to most of the UN missions were haggled over until late Saturday night, June 30, to meet a July 1 deadline. Apparently, demands by Russia and China on policy language and issues like funding human-rights posts held up decisions, said one diplomat.

Another person knowledgable about the committee said it was rare for Russia and China to have worked so closely in the Fifth on many matters. Recent media reports that China and Russia wanted to defund human-rights posts in peacekeeping missions caused a stir but some diplomats contend this demand was a strategy to extract other gains. Ultimately, the human-rights posts in peacekeeping missions were not eliminated but no new ones will be created, according to several diplomats.

China also insisted that Guterres submit yet another report on each of the two reforms — peace and security and management — in the fall, to be considered again by the General Assembly, before the new structures are to be set up. This action would give China another chance to reject or water down the reforms.

Not all of the details of Guterres’s reform proposals were accepted or even decided on by the Fifth Committee as of late Sunday night, as delegates continued debating technical points, such as where to place procurement services in UN management. Yet numerous delegates confirmed throughout the weekend that the main aspects of Guterres’s package would be informally approved by consensus.

As a South Asian delegate said, No one has the courage to reject Guterres’s proposals.

If the majority of the General Assembly adopts the peacekeeping budget brokered in the Fifth Committee, then, come January 2019, the Department of Management and Department of Field Support (the latter created in 2010 to administer peacekeeping operations) will fold into a new Department of Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance and a separate Department of Operational Support.

The departments of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and Political Affairs (DPA) will become the departments of Peace Operations (DPO) and Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA), respectively.

A key part of the reform package — establishing three global hubs, in Budapest, Mexico City and Nairobi — to handle back-office work for the UN Secretariat (which is led by Guterres) and peacekeeping operations was punted to the General Assembly session in 2019.

Since the start of his five-year term in January 2017, Guterres has been pressured by powerful member nations, first and foremost the United States, the largest financial donor to the UN, to transform the world body into a more cost-effective organization. That includes reducing overlapping responsibilities and bureaucratic bottlenecks as well as devolving decisions over issues such as procurement and personnel to less centralized and less expensive office sites, closer to the work being done.

But whether the authority of the UN can be decentralized to the extent that Guterres envisioned while remaining accountable to the 193 member nations that govern the Secretariat could pose a challenge for implementing new reforms. The use of the Internet, however, could make back-office work transparent.

The Secretariat’s unique governance means it cannot operate like a corporation or even like the office of the UN high commissioner for refugees, a sprawling agency that Guterres led for 10 years before he was selected secretary-general by the Security Council in late 2016. The refugee agency is a model that some delegates and UN staff members feel he is overly loyal to in his role heading the UN.

But greater transparency, efficiency and accountability and what some call a “results based” approach to fulfilling mandates have been demanded, in particular from the US, many European nations, some Latin American countries and Japan.

“It will be a complete shift in how the Secretariat is run,” said a UN official who has been assigned with shepherding reforms through the General Assembly committees. “To appreciate how massive the shift, one needs to understand how the Secretariat is run.”

Under the new reforms, peacekeeping and political field missions are to move under the new Department of Peace Operations, which will be an outgrowth of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations — or DPKO — led by a French under secretary-general for more than two decades. That will include the 11 field-based “special political missions” (including in Afghanistan, Colombia, Iraq, Libya and Somalia), which have been run by the Department of Political Affairs for the past decade by an American.

The US and Japan, however, were expected to try to keep the political missions in Afghanistan (called Unama) and Iraq (Unami) under American purview by leaving them in the political affairs office — soon to become the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs — rather than move them. Guterres had proposed the latter. As of late night July 1, the Fifth Committee was still debating that decision.

Peacekeeping missions, led by special representatives appointed by the secretary-general, are to be given far more authority over their own spending, a responsibility currently held by the Department of Management in New York.

The shifts in structure and responsibilities in the peace and security and management pillars were to be cost neutral. The “expert” committee on budgets, known by its acronym ACABQ (Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions), said in its report to the Fifth Committee delivered in mid-May that it “would have expected some efficiencies to be derived from a restructuring initiative of this magnitude.”

The ACABQ takes the first sweep of the secretary-general’s proposals before they are negotiated in the Fifth Committee. Resolutions issued by the committee are usually rubber-stamped by the greater General Assembly.

The peacekeeping mission in South Sudan, welcoming the release of former child soldiers in Yambio, part of a new phased program in which the country’s armed factions are letting such children go. Eighty-seven of the 311 children released in March 2018, above, were girls. The mission’s budget is likely to be slashed under UN reform measures.

Africa’s 54 nations worked valiantly as a bloc to obtain more advantages from the peacekeeping reform, as most peace operations are deployed there, such as more representation in New York headquarters. They were concerned that they were going to lose out in Guterres’s proposed “single regional political-operational structure” to be shared by the two new departments.

Under the current arrangement in the Department of Political Affairs and the Department of Peacekeeping Operations, four divisions are devoted to Africa. The new structure has three; African delegates argued for five. (That decision hadn’t been made yet, either.)

“It will be a reformette,” a Francophone African delegate predicted of the peace and security pillar reform, speaking on background. In early May, he said the Africans intended to hold the reform package hostage during the talks, until they received benefits such as better job representation in headquarters.

The US, a big backer of Guterres’s reforms, was predicted to have argued for relatively small budget cuts in the peacekeeping missions and management sectors, which put together ended up being substantial. A US delegate expressed dissatisfaction early on in open budget committee discussions that the secretary-general’s plan to devolve administrative functions from expensive headquarters like New York to new hubs was inadequate in terms of functions to be moved.

The Americans, however, dictated the placement of US-made generators on peacekeeping operations, according to an African diplomat.

The US and many other countries have been pushing the reform process ever since Guterres proposed them in 2017. In other areas, the US has been taking a highly critical approach to the UN under the Trump administration, including leaving the UN Human Rights Council in June and dropping out of the Iran nuclear deal in May. The latter agreement was approved by the UN Security Council, including by the Americans, under the Obama administration.

The US and Europeans and many other countries had supported Guterres, a former Portuguese prime minister, as the “reform candidate” for secretary-general, ever since he ran for the post, in 2016. (He was selected by the Security Council in October that year.)

Anticipating the budget committee process and keenly aware of US goals to cut funding to the peacekeeping missions, the Department of Peacekeeping Operations has been conducting critical reviews of its operations before the current Fifth Committee budget decisions were made. The reviews have not been made public or made available to Security Council members, a European diplomat said.

“The Secretariat has improved its reporting and transparency and execution of budgets,” said a delegate from Europe who works on the Fifth Committee, speaking on background. “The US needs to keep pressure on the Secretariat. I wouldn’t panic about it.”

He said that the European Union and the US share “a convergence of views,” even though the US asked for deeper cuts than Europe on peacekeeping. “But that is not the case with Russia and China,” which he said favored cutting human-rights posts, drones and fewer security improvements for peacekeepers.

There was also pushback from the Group of 77 — led by Egypt with Russia and China — who were not keen on decentralization, although some troop-contributing countries and countries that host peace operations could benefit from increased UN spending in the field.

“Member states must control the reform process,” the Russian delegate said as negotiations began in the Fifth Committee in May.

China, the largest troop-contributing country among the permanent-five members of the Security Council (Britain, France, Russia and the US) and the second-largest financial contributor to peacekeeping, tended to speak with African nations. Its delegate said there “should be no time limit on reforms.”

The General Assembly recently approved a provisional change from biennial to one-year budget cycles, a move that the G77 generally favored as giving smaller countries more opportunities.

Usually in May, the Fifth Committee meets for a month to review budget proposals for each peacekeeping operation. It’s a packed time, requiring reviews of hundreds of documents and horse trading among members over everything from aircraft to a single, junior-level post.

But this May, the committee was handed the additional major task of approving the implementation of Guterres’s proposals on peace and security, management and related restructuring. By late June, the clearly exasperated members of the committee were dealing with everything from the fine points of internet technology to a $27 raise for peacekeeping troops when it began negotiations on the 250-page report on management reform.

Whether by design or by default, many of the Secretariat documents integral to the committee’s work came in late — some three weeks after the session closed at the end of May — as committee members scrambled to acquaint themselves not only with the intricacies of individual peacekeeping missions but also with the largest reorganization of the UN in recent history. The management reform proposal alone was some 250 pages long.

This would be “the most decisive session of the Fifth [Committee] in decades,” Lill-Ann Bjaarstad Medina, a Norwegian delegate, said at the session’s opening in May.

Most Fifth Committee delegates serve only two-to-three year terms, so the learning curve was already steep. At their epic session last year, when the US threatened major cuts to the general operating budget, delegates spent the night sleeping on the plush furniture in the Qatari lounge in UN headquarters. That happened to some extent this year, with sessions lasting through dawn and resuming hours later. On June 30, delegates went home around 5 A.M. and returned around noon to finish hashing out the budgets of peacekeeping missions late into the night. They returned on July 1 to tackle the remaining issue of reform proposals.

The General Assembly had already approved, in theory, the secretary-general’s proposals for the peace and security and management pillar reforms, along with major reforms to the UN’s development system. Streamlining the latter will give new powers to the field-based “resident coordinators,” who will report directly to the deputy secretary-general, Amina Mohammed, a Nigerian.

Robert Piper, an Australian, will lead the transition team of the new development system. He is currently the officer-in-charge of the Bureau of External Relations of the UN Development Program.

Several delegates who were interviewed for this article noted Guterres’s personal approach to the permanent representatives (or ambassadors) to the UN, spending three hours with them and their deputies in May to review the reform proposals again. Some delegates remarked that the PRs, as they are known, would give the benefit of the doubt to Guterres over the advice of “experts” on the General Assembly budget committees.

“The PRs are more impressed with him than their capitals,” a delegate from the Middle East said.

But not all of Guterres’s proposals flew on the committee: the Global System Delivery Model, a cornerstone of the reforms, establishing the three regional hubs — in Budapest, Nairobi and Mexico City — was resisted. Some delegates said that Guterres failed to explain his choice of these hubs and the impact of cutting 684 posts and related activities from current UN sites.

Uganda stood to be the biggest loser in this regard, as its Regional Services Center in Entebbe has been expanding since its establishment in 2010 to include nearly 450 staff members, more than half of them Ugandans. The base provides logistical and administrative support to most of the peace operations in Africa. Closing or reducing the base could cost the UN up to $25 million, the Ugandan delegate told the Fifth Committee. Other delegates were also dubious, including from Switzerland — Geneva is home to another UN headquarters — who said the hub proposal “raised big questions.”

The staff unions have been saying little about the pending reforms: their recent concerns have been pay cuts to staff in Geneva, Tokyo, Bangkok and elsewhere.

Worries about “the challenges faced in meeting management reforms, which impact not only staff, but also service delivery,” were discussed at the May assembly in Bangkok of the Coordinating Committee for International Staff Unions and Associations.

Among staff members in New York, talk of reforms can evoke a sense of plus ça change — shrugs. Some senior management officials have expressed horror at what they see as the pending dissolution of their department.

On the other hand, the first stage of peace and security reform is underway, as staff members in the Department of Political Affairs and Department of Peacekeeping Operations have moved to the same floor. That change has not resulted in the two groups sharing their portfolios or substantially integrating their work, some people told PassBlue.

This article first appeared on PassBlue and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.