|

From left to right: Moderator Professor Daisaku Higashi (University of Tokyo), Commentators Professors Mitsugi Endo(University of Tokyo) and Saburo Takizawa (Toyo Eiwa Jogakuin University), Professor S. Hasegawa (Hosei and UN University)

|

|

The United Nations has called on its member states for more financial and human resources contributions to and active participation in UN peacekeeping and peacebuilding missions. In its annual session to be held next week in New York, the Peacebuilding Commission is taking up the challenge of securing “sustainable support for peacebuilding.” The background paper prepared by the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO) asserts “Effective and sustainable systems for resource mobilization are a key element of the consolidation of peace in countries emerging from conflict. The financial, institutional and human capital aspects of resource mobilization needs to be addressed in its national and international components, with due consideration for the principle of national ownership and the fundamental objective of providing sustainable support to improve the lives of affected populations” (Annual Meeting of the Peacebuilding Commission, 23 June 2014). As much as I agree with the UN Peacebuilding Commission about the need for financial and human resources contributions from the international community, I find it imperative that we direct more attention to the formation of national leadership that can respond to competing and conflicting demands for achieving stability and peace in a post-conflict country.

Today, I wish to share with you an insight into the paradoxical – competing and conflicting – challenges that often compete in countries emerging out of conflicts. I do so based on my experiences of engaging in peacekeeping and peacebuilding operations in Cambodia, Somalia, Rwanda and particularly in Timor-Leste where I spent more than four years as Special Representative of the Secretary-General as well as the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator of the UN system.

1. As the role of leadership is the theme of my talk today, I should inform you about the leaders I personally dealt with in several conflict-prone and post-conflict countries. In Somalia, I found war lords who put their personal interest and agenda above the national interest. In Rwanda, I met Paul Kagame who placed national security above all.

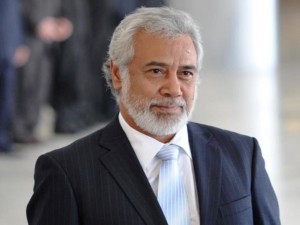

2. In Timor-Leste, I found a group of leaders who are committed to national interest and unity. Xanana Gusmão was the national leader whom the majority of Timorese trusted and even believed in. “He was a fighter who exuded personal warmth, dealing with people with trust and affection, loving them and enjoying being loved. This relationship was most important to him, for his frame of reference was Timorese society and people.” (Hasegawa, Primordial Leadership, 2013, P.75).

3. Ramos-Horta’s frame of reference was the international community. “He was a cosmopolitan statesman who thought in terms of universal values and principles. These were rare qualities to find on a remote island in the Indonesian archipelago. Ramos-Horta was fully acquainted with the norms and standards developed at the United Nations. He was also up to speed with other forms of emerging global governance. He was cognizant of the principal needs for the Timorese people: the right of self-determination, protection from political persecution and other human rights that all people are entitled to” (Hasegawa, Primordial Leadership, 2013, p.15).

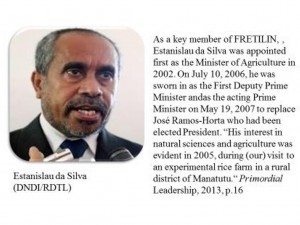

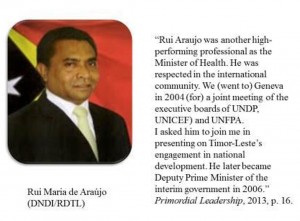

4. Mari Alkatiri, the first Prime Minister, was “an intellectual with a strong spirit of independence and possessing enormous pride and confidence…A tireless worker who was relentless in the pursuit of his goals and interests, he worked day and night towards the end of his term. His approach was to safeguard his authority and independence at any cost, and he did not mind being disliked or unloved; his frame of reference was himself.” (Hasegawa, Primordial Leadership, 2013, pp.74-75). Francisco ‘Lú-Olo’ Guterres, demonstrated his commitment to national interest and unity when the armed struggles among security personnel got out of control. He along with the three other senior most leaders of the country when he signed a letter on 24 May 2006 requesting the intervention of multilateral forces to stop the armed fighting. (Hasegawa, Primordial Leadership, 2013, pp.144 and 160 footnote 30). FRETILIN has two other leaders who were technocrats, highly educated and trained in health and education, Rui Maria de Arujo and Estanislau da Silva. Following the security crisis of 2006m they were appointed Deputy Prime Ministers. In 2015, Rui Arujo was appointed Prime Minister and Estanislau da Silva Deputy Prime Minister and Coordinating Minister for economic and agricultural matters.

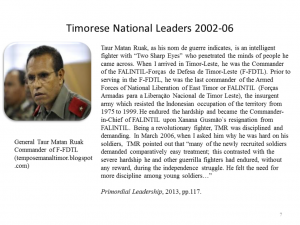

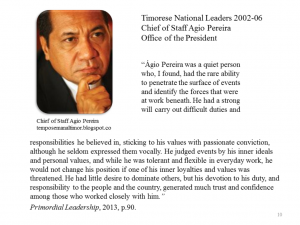

5. During my assignment in Timor-Leste, I found two other leaders who excelled in their devotion to the national unity and interest. They were F-FDTL Commander General Taur Matan Ruak who came the President in 2012 and Mr. Agio Pereira, then Adviser to President Xanana Gusmão. Agio came the second senior most minister in the Government of Timor-Leste in 2015. Agio proved highly committed to national interest and unity and generated trust and confidence among those who worked closely with him.

6. Timor-Leste was fortunate to succeed in building peace with not only the sustained support of the international community but also the availability of national leaders who were committed to national interest and unity above their personal interest and power. National leaders who believed in truth and friendship with Indonesians who had killed one fifth of their people in 24 years; leaders who remember the past but look more to the future; who cared about the people, who respected the international norms and principles but also knew the need to respect local values and customs that need to be integrated. And the people who have courage to step down before it’s too late to hand over the power of governance to the younger general.

7. According to the democratic peace doctrine, it is sometimes necessary to depose a dictator or an authoritarian regime by force to realize democratic governance. But a democratic system installed to replace the dictator never survive unless the minimum stability of the state is secured by a ruler with absolute power.

8. As Fredrik Hegel observed more than two hundred years ago, the state of Selbstentfremdung in France, we have seen recently “the alienation of the self” Egypt after the Arab Spring. Yet, Selbstentfrendung is an unavoidable path before the arrival of democratic governance with the transformation of the self.

9. If peace and stability cannot be realized without reconciliation, the rule-of-law advocates assert that justice can. That’s what Immanuel Kant said, “perpetual peace requires categorical justice.” Peacekeepers and peacebuilders pursue this John Rawls’ norm and his systemic approach by practicing the institutional capacity building of a fragile country believing that a strong institution anchored in perfect justice is a best approach for sustainable peace and stability.

10. Yet, we have learned from Mandela that truth is more powerful than justice for truth can heal the wounds of victims as much as justice, while justice without truth is no justice at all. Justice with truth is more achievable in the practice of restorative justice over retributive justice as I have witnessed in Rwanda and Timor-Leste. Does this mean that Immanuel Kant and John Rawls were wrong? No, they were right but the application of their prescription must respond to time and space.

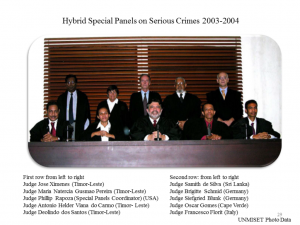

11. “A major development occurred on 10 May 2004 at 3:35 p.m. when Judge Phillip Rapoza of the Special Panels for Serious Crimes issued an arrest warrant for retired General Wiranto, who was then running for President in Indonesia. The former Minister of Defense and Security of Indonesia, and Commander of the armed forces, had previously been indicted on 24 February 2003. General Wiranto, along with several high-level military officers and the former Governor of East Timor, had been accused of crimes against humanity committed in Timor-Leste in 1999” (Hasegawa, Primordial Leadership, 2013, p.181). The Timorese leaders, however, insisted that the trial of General Wiranto does not take place as they did not want to pursue the retributive justice and preferred to establish a “truth and friendship” commission with Indonesia.

12. To know the truth, you must find it based on reason and perception, or knowledge arrived at by rational reasoning and experience. To govern a fragile and conflict-prone country, we must find or nurture national and local leaders who can incorporate external and universal values, norms and standards and adopt and integrate them with local values and customs.

13. The lessons I learned from my peacekeeping and peacebuilding support assignments in Cambodia, Somalia, Rwanda and Timor-Leste revealed the need to address the short and long term requirement of conflict-prone and post-conflict fragile states. Local institutional capacity building is a must for a long run and the rule of law is essential for achieving a peaceful and stable society. But, it is equally important to try to secure conscientious leaders who are committed to national interest and unity as well as basic human rights.

14. Rather than relying solely on governmental rules and regulations to bring order to the country, its leaders appealed to the citizens’ strong emotional ties to the homeland and their sense of national unity. This primordial leadership in post-conflict Timor-Leste facilitated a widespread feeling of ownership and accountability, helping the country’s leaders successfully turn security crises in 2006 and 2008 into opportunities for fostering respect for democratic governance. This change in mindset and the ensuing spirit of national unity were instrumental in achieving peace and stability—more than the externally induced, exclusive efforts in building institutional frameworks for the rule of law and democratic governance.

15. While the application of democratic principles is necessary in the long term, it alone is not sufficient for building sustainable peace in an immediate post-conflict period. The leadership of Timor-Leste was committed to national interest, identity, and unity; it was able to harmonize the universal ideals and principles of governance with local community values and customs. It had the passion and courage to empower others, the willingness to pursue the future rather than the past, and the capability to transform the mind-set and mentality of people. Without those characteristics, success would have been very much in doubt.

16. For peacebuilding to succeed, in responding to competing demands for our support, it is imperative that the United Nations pay as much attention to the leadership requirement as we do with the institutional capacity building focused on rule of law and human rights.